How drugs intended for patients ended up in the hands of illegal users: ‘No one was doing their job’

By Lenny Bernstein, David S. Fallis and Scott Higham October 22

For 10 years, the government waged a behind-the-scenes war against pharmaceutical companies that hardly anyone knows: wholesale distributors of prescription narcotics that ship drugs from manufacturers to consumers.

The Drug Enforcement Administration targeted these middlemen for a simple reason. If the agency could force the companies to police their own drug shipments, it could keep millions of pills out of the hands of abusers and dealers. That would be much more effective than fighting “diversion” of legal painkillers at each drugstore and pain clinic.

Many companies held back drugs and alerted the DEA to signs of illegal activity, as required by law. But others did not.

Collectively, 13 companies identified by The Washington Post knew or should have known that hundreds of millions of pills were ending up on the black market, according to court records, DEA documents and legal settlements in administrative cases, many of which are being reported here for the first time. Even when they were alerted to suspicious pain clinics or pharmacies by the DEA and their own employees, some distributors ignored the warnings and continued to send drugs.

“Through the whole supply chain, I would venture to say no one was doing their job,” said Joseph T. Rannazzisi, former head of the DEA’s Office of Diversion Control, who led the effort against distributors from 2005 until shortly before his retirement in 2015. “And because no one was doing their job, it just perpetuated the problem. Corporate America let their profits get in the way of public health.”

A review of the DEA’s campaign against distributors reveals the extent of the companies’ role in the diversion of opioids. It shows how drugs intended for millions of legitimate pain patients ended up feeding illegal users’ appetites for prescription narcotics. And it helps explain why there has been little progress in the U.S. opioid epidemic, despite the efforts of public-health and enforcement agencies to stop it.

At the peak of the crisis, the DEA retreated from the battle. A Post investigation published Sunday revealed that beginning in 2013, some officials at DEA headquarters began to block and delay enforcement actions against wholesale drug distributors and others, frustrating investigators in the field.

Several former DEA officials told The Post that the shift in approach undercut the cases against some of these distributors, who were ignoring signs that their customers were ordering suspicious quantities of narcotics.

“We could not get these cases through headquarters,” said Frank Younker, a DEA supervisor in the Cincinnati field office who retired in 2014 after a 30-year career. “We were trying to shut off the flow, and we just couldn’t do it.”

The 13 companies include Fortune 25 giants McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen, which together control about 85 percent of all pharmaceutical distribution in the United States. They also include regional wholesalers such as Miami-Luken and KeySource Medical, both based in Ohio, as well as Walgreens, the nation’s largest retail drugstore chain. Many of the distributors are tiny operations with just a few employees.

It is not clear how many other cases exist. Because the DEA handles its enforcement actions administratively, few details surface unless the agency or the company discloses them, or if one side appeals in civil court.

The DEA declined to disclose how many enforcement actions it has brought against distributors, requiring a Freedom of Information Act request that The Post filed in April. The request is pending. The DEA also would not make any officials available to discuss this article, but it provided a statement from acting administrator Chuck Rosenberg defending the agency’s enforcement actions.

“We now have good folks in place and are moving in the right direction,” he said.

Some of the 13 companies have fought the DEA’s enforcement efforts in court and in hearings before the agency’s administrative law judges. Except in two pending cases, all have lost or settled. Using its civil authority, the DEA stopped the flow of narcotics from some company warehouses, and U.S. attorneys levied fines totaling more than $286 million.

Most of the 13 wholesalers involved in these cases declined to be interviewed. In court filings and congressional testimony, they said they have developed large and sophisticated systems to help prevent drug diversion. They have complained that it is difficult to police the activities of far-flung drug dispensers and have noted that drugs could not be sold to illegal users without prescriptions written by corrupt doctors. They also criticized the DEA’s past approach to the problem as punitive and its rules as vague and confusing.

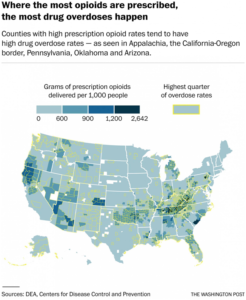

But the problem is clearly ongoing. Prescription narcotics cause more overdose deaths every year than any street drug, including heroin. The painkiller epidemic has taken 165,000 lives since the turn of the century, with the number of deaths soaring from 3,785 in 2000 to 14,838 in 2014.

Opioid overdoses, mainly from prescription drugs, are also the leading cause of the recent unexpected rise in the mortality rate of middle-aged white Americans, particularly women in rural areas, after decades of steady decline.

But it is impossible to estimate how much of the opioid supply is siphoned away to illicit use.

“No one knows, because it’s impossible to track what happens to an individual prescription once it leaves the pharmacist,” said Susan Awad, director of advocacy and government relations for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

One of the first wholesalers targeted by the DEA under its “Distributor Initiative” was Southwood Pharmaceuticals, a small company based in Lake Forest, Calif., that sent controlled substances to Internet pharmacies. Because these online businesses typically allowed people to obtain drugs without being seen by a doctor, they were ripe for abuse.

In 2005, for example, Southwood supplied one Florida online drugstore, Medipharm-Rx, with 8.6 million doses of hydrocodone — the opioid found in Vicodin and Lortab, according to the DEA.

But Southwood failed to file a single suspicious order report, even after the DEA warned the company in July 2006 about the growth in the volume of its shipments. The DEA had seen the trend in its own monitoring of drug-sales data.

“Even after being advised by agency officials that its internet pharmacy customers were likely engaged in illegal activity, [Southwood] failed miserably to conduct adequate due diligence,” Michele Leonhart, then the DEA’s deputy administrator, wrote in a 2007 decision to revoke the company’s license to distribute narcotics.

“The direct and foreseeable consequence of the manner in which [Southwood] conducted its due diligence program was the likely diversion of millions of dosage units of hydrocodone,” Leonhart wrote, adding that the company had reason to know that the 44 million doses of hydrocodone it distributed were probably being diverted.

That amount would provide a 30-day supply of narcotics for everyone in the city of Dallas, according to Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit management company.

Southwood got out of the business of selling controlled substances and six years later lost its pharmacy license in California.

The company’s president, John Sempre, recently told The Post that the company did not understand at first that it was supplying Internet pharmacies. He said it is very difficult for companies to monitor the sales of faraway retailers.

“If companies like McKesson can’t control it, what does that tell you?” Sempre asked.

In 2008, McKesson, the nation’s largest drug distributor, settled a case that accused three of its U.S. warehouses of failing to report hundreds of suspicious orders from Internet pharmacies. “As a result, millions of doses of controlled substances were diverted from legitimate channels of distribution,” the Justice Department said in a news release. The company paid a $13 million fine to U.S. attorney’s offices in Florida, Maryland, Colorado, Texas, Utah and California.

“By failing to report suspicious orders for controlled substances that it received from rogue Internet pharmacies, the McKesson Corporation fueled the explosive prescription drug abuse problem we have in this country,” Leonhart, then the acting DEA administrator, said in a statement at the time.

Seven years later, after being caught up in a second diversion case, McKesson agreed to pay a $150 million fine and accepted license suspensions at four warehouses, according to a company filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. No other details of that case have become public, and both the company and the DEA declined to discuss it.

A McKesson spokeswoman said in a statement to The Post, “We welcome the ongoing dialogue with the DEA aimed at developing effective controlled substances monitoring programs and successfully mitigating prescription drug abuse and diversion.”

AmerisourceBergen, another member of the so-called Big Three distributors, lost its license to send controlled substances from an Orlando warehouse on April 24, 2007, amid allegations that it was not controlling shipments of hydrocodone to Internet pharmacies. The facility was back in business by August of that year and did not pay a fine, according to a company spokeswoman.

Few details of the case have surfaced.

Cardinal, the third member of the Big Three, paid a $34 million fine in 2008 after seven of its warehouses across the country filled thousands of suspicious orders from Internet pharmacies without reporting them, despite an earlier warning from the DEA, according to a Justice Department news release.

On Oct. 5, 2010, when Cardinal investigator Vincent Moellering visited Gulf Coast Medical Pharmacy, a drugstore in Fort Myers, Fla., he found evidence of diversion everywhere, records show, including suspicious customers who came in groups to fill their prescriptions.

The pharmacy’s owner told Moellering that he could sell even more narcotics if Cardinal would supply them, according to Moellering’s report, which the DEA introduced in a court proceeding.

Moellering labeled the drugstore “high risk” and wrote: “I am not convinced that the owner is being forthright pertaining to his customers’ origin or residence. I have requested permission to contact DEA to resolve this issue.”

But Cardinal didn’t notify the agency or cut off Gulf Coast’s drug supply, the DEA contends. Instead, the shipments kept going out. In 2011 alone, Cardinal sent more than 2 million doses of oxycodone to Gulf Coast. Cardinal typically shipped 65,000 doses of the opioid annually to comparable pharmacies, the DEA said.

Even as Cardinal was increasing its shipments to Gulf Coast, another wholesale drug distributor, H.D. Smith, was cutting off its supply of painkillers to the pharmacy. Smith took action after one of its compliance officers visited Gulf Coast and found “impaired and lethargic” customers “with glassy eyes” in November 2010, a few weeks after Moellering’s visit, court records show.

The Smith inspector learned that the pharmacy filled 300 prescriptions a day, nearly half for controlled substances. Smith considered anything over 20 percent to be a red flag.

Gulf Coast owner Jeffrey R. Green and manager Karen S. Hebble sometimes waited after hours to sell narcotics, even without a pharmacist present, court records show.

Drug dealers said they brought groups of fake patients — known in the trade as “spuds” or “skidoodies” — to Gulf Coast to fill bogus prescriptions obtained from cooperating prescribers, court records state. They always paid cash.

One drug dealer would call ahead to make sure Gulf Coast had enough pills for his fake customers. Cardinal only stopped shipments to Gulf Coast in October 2011, shortly before the DEA demanded information from the distributor. The next month, Gulf Coast surrendered its license.

Green and Hebble were ultimately convicted in federal court of conspiracy and money-laundering charges.

Cardinal contended that volume of drug sales alone is not an accurate measure of lack of compliance. The company noted that Gulf Coast served a hospital complex and hundreds of physicians.

In 2012, Cardinal settled the administrative case, but no fine has been levied. Negotiations are ongoing, according to a federal prosecutor and the company.

In a statement to The Post, Brett Ludwig, Cardinal’s vice president of public relations, said the company deploys “advanced analytics, technology, and teams of anti-diversion specialists and investigators who are embedded in our supply chain. This ensures that we are as effective and efficient as possible in constantly monitoring, identifying, and eliminating any outside criminal activity.”

At Walgreens, an employee at one of the 13 warehouses the drugstore chain operated in the United States grew suspicious of the large orders being sent to some of its pharmacies, court records show.

Kristine Atwell, who managed distribution of controlled substances for the company’s warehouse in Jupiter, Fla., sent an email on Jan. 10, 2011, to corporate headquarters urging that some of the stores be required to justify their large quantity of orders.

“I ran a query to see how many bottles we have sent to store #3836 and we have shipped them 3271 bottles between 12/1/10 and 1/10/11,” Atwell wrote. [A bottle sent by a wholesaler generally contains 100 doses.] “I don’t know how they can even house this many bottle[s] to be honest. How do we go about checking the validity of these orders?”

Walgreens never checked, the DEA said. Between April 2010 and February 2012, the Jupiter distribution center sent 13.7 million oxycodone doses to six Florida stores, records show — many times the norm, the DEA said.

In March 2011, the situation became so alarming at two Walgreens drugstores in the small town of Oviedo, Fla., that Police Chief Jeffrey Chudnow wrote to the company’s top executives, Alan G. McNally, who was chairman; and Gregory D. Wasson, then the president and chief executive.

Chudnow asked that they prohibit Walgreens pharmacists from filling orders where the quantities of narcotics were split over two prescriptions.

“These types of prescriptions overtly denote misuse and possible street sales of these drugs,” Chudnow wrote. He said he never heard back from the executives.

In 2012, the DEA launched a six-month investigation of Walgreens’s Jupiter facility. The probe found that Walgreens failed to maintain an effective system for detecting suspicious orders or reporting them to the DEA.

Even when suspicious orders were identified, the warehouse often shipped the drugs anyway, without making inquiries, the DEA said in court papers. A company spokesman said Walgreens would have no comment on the case.

Walgreens settled with the DEA in 2013, agreeing to pay an $80 million fine — a record for a diversion case at the time. The company acknowledged that its “suspicious order reporting for distribution to certain pharmacies did not meet the standards identified by DEA.”

In 2013, DEA officials at the agency’s headquarters began requiring a higher burden of proof before investigators in the field could take enforcement action. One case that was underway became entangled in that shift, according to interviews and records.

Beginning in 2011, the DEA had repeatedly warned Miami-Luken, an Ohio-based distributor, about suspicious sales of opioids, according to Jim Geldhof, then the agency’s program manager in Detroit.

“We went to management of the company and told them they have to look at their sales. They are pretty extraordinary,” said Geldhof, who retired in January after more than four decades with the agency. “We spoke to them on multiple occasions, and we were pretty much ignored.”

Yet investigators couldn’t persuade lawyers at DEA headquarters to allow them to take action.

Geldhof said orders to show cause that he requested in 2013 were not issued until November 2015.

“It sat there for two years. I don’t know why there was a delay,” Geldhof said. “We went back and forth. The ball was always moving. We had all of this going on, overdose deaths, what part of this are we not getting them to understand. We said, ‘You tell us what you want and we’ll give it to you.’ ”

Inside Miami-Luken headquarters, employees had also seen troubling signs. Two of them sent word up the chain. A pharmaceutical buyer and a customer-service representative were concerned about large oxycodone orders by a southern Ohio pain clinic.

The warnings reached senior company officials, including then-chief executive Anthony Rattini. But little changed.

Cindy Willet, the senior pharmaceutical buyer, told investigators in 2015 that she eventually “stopped talking to [Rattini] about her concerns because he wasn’t doing anything about it. It was as if it was falling on deaf ears. Tony never stopped an order.”

The pain clinic, Unique Pain Management, was based in Wheelersburg, Ohio, a town of 6,500 at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. The clinic was run by a father-daughter team of physicians, John and Margy Temponeras. Between December 2009 and June 2010, the clinic’s monthly orders of oxycodone rose from 67,800 doses to 104,400. Miami-Luken did not investigate the surge, according to the DEA.

Despite signs that something was amiss, “Miami-Luken not only continued to ship Dr. [Margy] Temponeras oxycodone, but also shipped increased amounts,” the DEA alleged.

But Margy Temponeras ordered so much OxyContin from Miami-Luken that in August 2010 she drew the attention of Purdue Pharma, the drug’s manufacturer. Purdue cut Miami-Luken’s OxyContin supply by 20 percent, prompting Miami-Luken to halt drug shipments to Temponeras, records show.

Last year, a federal grand jury indicted the Temponerases and a pharmacist on charges that they conspired to illegally sell medication, alleging that at least eight people had died of overdoses connected to the drugs.

Three of those people died while the clinic was receiving drugs from Miami-Luken between November 2008 and August 2010, according to the indictment and DEA records. It is unclear whether Margy Temponeras also purchased drugs from other distributors, or whether any of those who died consumed drugs distributed by Miami-Luken.

The Temponerases are scheduled to stand trial early next year. Their attorneys declined to comment. An attorney for the pharmacist, Raymond Fankell, who is also scheduled to stand trial next year, said Fankell’s involvement was limited to helping Margy Temponeras set up the dispensary in her office and to filling her prescriptions at his drugstore.

During one of their interviews with Rattini, DEA investigators asked how the company documented suspicious orders. Rattini pointed to his compliance officer, who put a finger to his head. “It’s all just up here,” he said.

The agency is now attempting to revoke Miami-Luken’s license. The company has asked for a hearing before a DEA administrative law judge and is battling the DEA in federal court over a subpoena for agency records.

Miami-Luken is one of two distributors identified by The Post whose cases are pending in civil court. Eleven other companies have agreed to settlements, taken corrective steps or given up their licenses to distribute controlled substances, records show.

“We’re taking this to a hearing because we strongly dispute the government’s characterizations,” said Richard H. Blake, an attorney for Miami-Luken.

The company said in court filings that it has purchased software to better identify suspicious orders and added staff to its compliance efforts. Its chairman, Joseph Mastandrea, intends to testify that he removed Rattini from his role supervising compliance “as DEA’s inquiries increased” and that he “realized that Mr. Rattini was not fulfilling the company’s DEA compliance obligations,” according to court filings.

Rattini did not return calls seeking comment. The chairman “will accept responsibility for the company’s past failings,” the court documents state.

Alice Crites contributed to this report.