https://training.northcentralhidta.org/default.aspx?menuitemid=96&menugroup=Training

All posts by admin

CanAm 2025 Sponsors

MSANI would like to thank the following 2025 Conference Vendors:

- Lens Equipment

- Detectachem

- Covert Track, a 3SI Company

- Glock Inc.

- North Central HIDTA

- Alex Pro Firearms

- Vortex Optics

- Skydio

- ALPHA Training, Tactics, and Sales

- Ensurity GPS

- RJ Wagner Marketing Inc. / Point Blank Enterprises

Sponsors:

- Midwest Machinery

- Schell’s Brewery

- Federal Ammunition

- Drip Drop

- Johnson Brothers

- MN Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA)

- MCTC

- MN National Guard Counterdrug Program

Past sponsors:

CanAm Lodging

Lodging is now available!

TF Commanders: Click here to reserve cabin lodging at Grand View Lodge

Individuals: Click here to reserve lodging at Grand View Lodge

CanAm 2025

Dates: May 21-23, 2025

Grand View Resort, Nisswa, MN

Minnesota Marijuana Hospital-Treated Poisonings for Children Under 4 Increased by 733% Over the Past Six Years

Rural Patrol Drug Interdiction

Monday, May 12 – Wednesday, May 14, 2025, Duluth, MN

The Midwest Counterdrug Training Center focuses National Guard capabilities and assets to facilitate professional development, mitigate training gaps, and increase counterdrug expertise in the LEA and CBO communities in order to build safe and strong communities

Flier: http://msani.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/5-12-2025-Rural-Patrol-Drug-Interdiction.pdf

CanAm Agenda Published!

Registered users can see the full agenda here: 2024 CanAm Agenda

Recriminalizing drugs; Oregon offers a cautionary tale

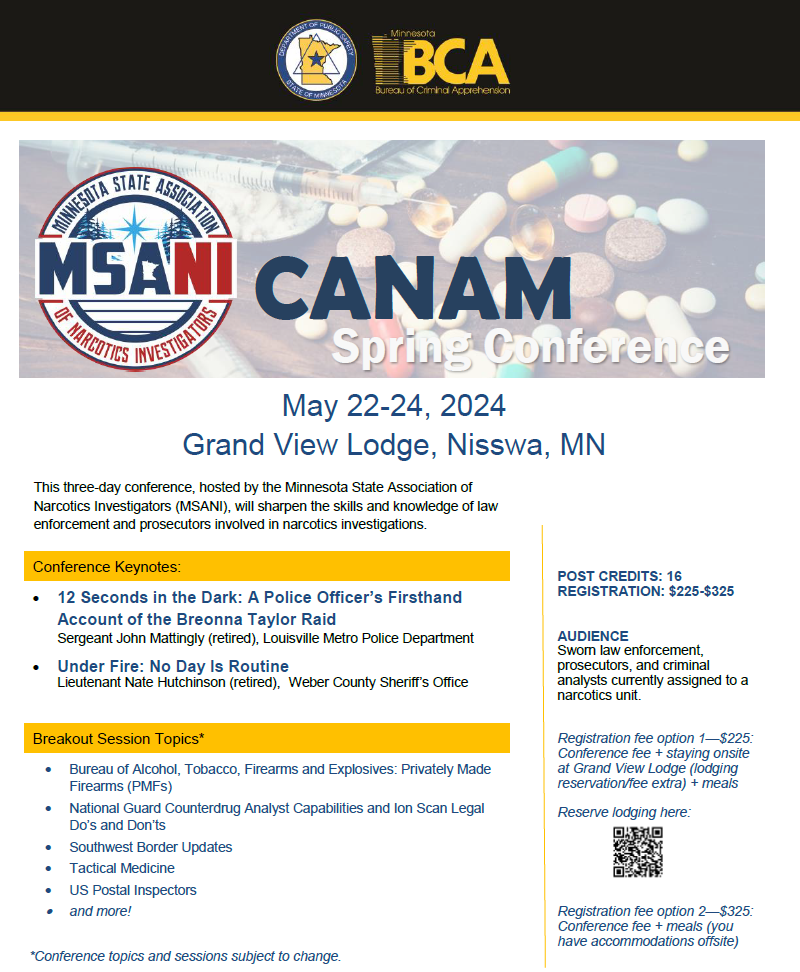

CanAm 2024

CanAm 2024 Registration is Live!

Registration for Lodging and Conference are live today.

BOTH are necessary for attendance; Lodging is through Grand View and the Conference/Training registration is through BCA.